Introduction

For over a decade, a series of crises have undermined the media’s ability to support democracy. Traditional business models have collapsed with the rise of the internet and social media platforms. Hyperpartisan news sites and disinformation have damaged readers’ trust in online content. At the same time, illiberal leaders in several democracies have developed sophisticated methods for silencing and co-opting the media.

These serious challenges have sparked new and ambitious approaches for sustaining journalism. Driven by necessity, a dynamic group of European media organizations are developing alternative business models, strengthening the craft of journalism, engaging younger and more diverse audiences, and building networks to defend against legal attacks. While their stories are distinct, lessons learned from their successes can inform future policy approaches to reviving independent media amid the twin forces of democratic backsliding and digital disruption.

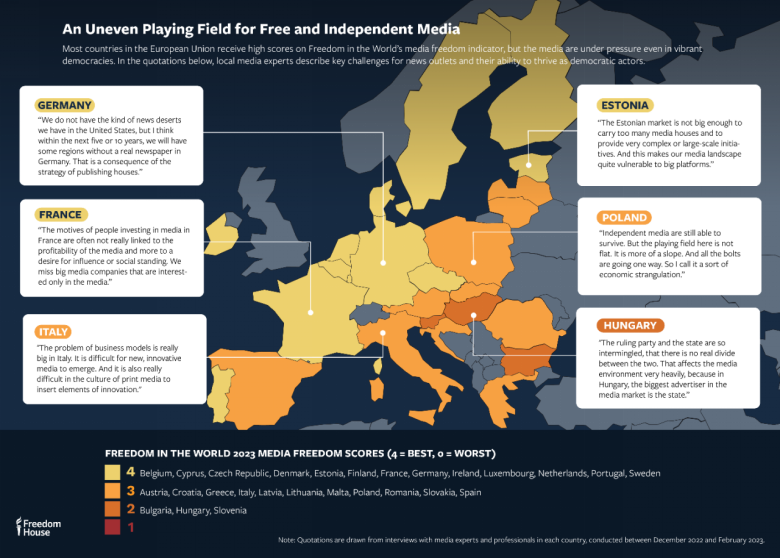

Freedom House conducted in-depth research and interviews with nearly 40 media professionals and experts in six countries: Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Poland. The countries vary by market size and by the health of their democracy, but all are part of the European Union (EU), where members are debating important regulatory measures to protect media independence and pluralism under a proposed European Media Freedom Act. Freedom House examined four conditions affecting the playing field for independent news media and their role in democracy: their ability to sustain themselves financially, reach and engage diverse audiences, earn public trust, and play a watchdog role.

The report found several areas of promise. In the face of economic coercion, Hungarian outlets such as Telex, Klubrádió, Átlátszó, Partizán, and Direkt36 have turned to crowdfunding, microdonations, and membership schemes, or formed nonprofit foundations to collect taxpayer donations. These efforts consciously use financial transparency to earn donors’ (and readers’) trust. Digital outlets like Mediapart and Les Jours in France and Il Post in Italy have also focused heavily on cultivating audience revenue, earning trust and credibility by embracing transparency and adhering to strong ethical standards.

Public service media have also reached out to new audiences. Estonia’s public broadcaster invested in a dedicated Russian-language channel to counter Moscow’s propaganda and deliver independent news to the country’s Russian-speaking population. In Germany, public broadcasters ARD and ZDF founded an online-only network that engages younger audiences, while some reputed outlets have garnered large followings on TikTok.

And, in environments where journalists face increasing legal and political threats, outlets have joined networks to defend themselves in solidarity rather than in isolation. For investigative projects in Poland, Hungary, and Italy, legal aid, cross-border investigations, and international advocacy efforts have provided safety nets against a deluge of frivolous lawsuits.

People gather at the “Free People, Free Media” protest on the Main Square in Krakow, Poland, in December 2021. (Photo credit: Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto)

While these bright spots hold promise, the challenges journalists and media managers face are broad and systemic. It will take holistic solutions to ensure environments where independent media can continue to flourish. The report concludes with a series of recommendations to European institutions, governments, funders, and civil society organizations. The learnings from this research have global implications for how democracies can revive media’s ability to play a constructive role in democracy.

The Changing Landscape for Media and Democracy in Europe

Attacks on the media have contributed to a decline in global freedom. In Freedom in the World, Freedom House’s annual assessment of political rights and civil liberties, the indicator for media freedom has declined more than any other during the past 17 years of democratic recession. In the European Union (EU), an increasingly uneven and fragile environment for free and independent media is testing the union’s ability to defend its founding democratic values. Even within established democracies, it has become more challenging for media organizations to uphold the kinds of journalism that help people make informed choices about their lives and communities, expose corruption, and encourage civic engagement.

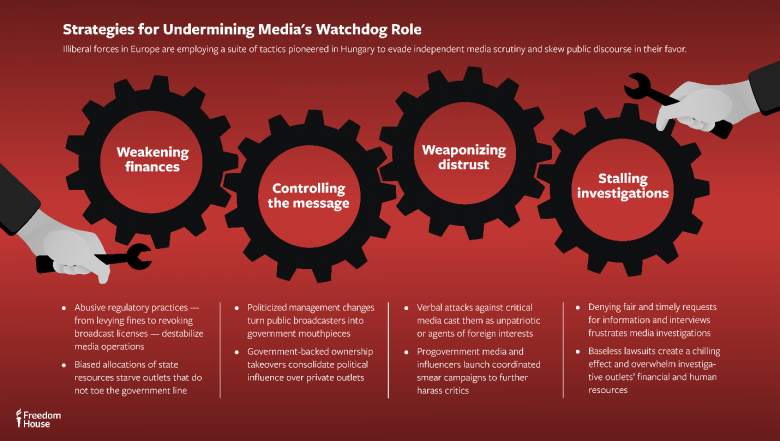

Over the past decade, some governments have deliberately skewed media landscapes in pursuit of self-serving political interests. The Hungarian and Polish governments stand out for attacks on media freedom and pluralism. Having once embraced their transition from communism to liberal democracy, in recent years they have significantly rolled back freedoms for independent media amid their broader dismantling of democratic checks and balances—all of which has taken place under the EU’s watch.

Hungary has become the only EU country rated Partly Free in Freedom in the World, and has joined the grey zone of “hybrid regimes” in Freedom House’s Nations in Transit report. The government’s hostility toward critical media has played a significant role in this deterioration. Since taking power in 2010, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Alliance of Young Democrats–Hungarian Civic Union (Fidesz) has implemented a series of constitutional and legal changes that have undermined the rule of law and consolidated control over state institutions. While privately owned independent media outlets still exist, the cards are heavily stacked against them in a landscape dominated by progovernment outlets that frequently smear the party’s political opponents and perceived critics. State advertising favors outlets that toe the party line, public service media is controlled by the government, and government allies have taken control over large segments of private media.

Poland’s media remains more vibrant than Hungary’s. Since 2015, however, Jarosław Kaczyński’s populist and socially conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party has exerted economic, legal, regulatory, and political pressure to destabilize outlets considered adversarial and recalibrate the landscape in its favor. The party has purged dissenting voices from public broadcasters, and has used state-owned companies to take over press distribution networks and regional media and to channel public advertising to outlets that support the PiS government. In its efforts to “repolonize” the media landscape, PiS has taken aim at foreign media ownership, and has redoubled pressures on the US-owned private television station TVN and its news channel TVN24, which is often critical of the government.

Countries that score higher on Freedom in the World’s indicator for media freedom include Estonia, Germany, and France. But even robust democracies that benefit from well-grounded journalistic protections, regulatory frameworks, and independent judiciaries are not without their own difficulties in sustaining vibrant news sectors that can engage audiences in the digital era and provide a diversity of high-quality content.

French media operate freely, and the landscape continues to boast a plurality of voices and political opinions at the national and local levels, yet public policies related to the media have struggled to keep pace with new digital realities. The state maintains one of the oldest press subsidy systems in Europe, but it has faced criticism for an outdated approach that favors established print outlets over newer digital entrants. Moreover, the rise of major media owners who also retain stakes in separate industries has fed growing public skepticism about the media’s independence. Public antagonism has been reflected in verbal and physical attacks against journalists during protests in recent years. This phenomenon has been most acute during coverage of the Yellow Vests protests, which began in 2018 and brought to light frustrations with the deepening gulf between ordinary people and the political establishment, including the journalistic elite.

Influenced by its totalitarian past, Germany has established strong safeguards to shield its media system from authoritarian power grabs. This includes a decentralized model for public service media that helps protect editorial independence and pluralism. While press freedom in Germany remains robust and self-regulation through the press council and press codes generally works well in practice, financial pressures have impacted media pluralism, especially local news production. Though traditional media still garner high levels of public trust, hostility amongst a more disengaged segment of the population has coincided with the rise of far-right populism. Protests have also increasingly become flashpoints for violence against journalists.

Estonia’s media sector has radically changed since the country’s formal independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. With just over 1.3 million inhabitants, Estonia’s smaller size limits its ability to diversify news production amid cost pressures and competition with international players. This has resulted in high levels of concentration among three main media groups: Estonian Public Broadcasting (ERR), and two owners in the private sector: Ekspress Grupp and Postimees Grupp. Moreover, the media market is characterized by long-standing “information bubbles” between the country’s Estonian and Russian speakers. Major channels of the Russian Federation attracted significant viewership among Estonia’s Russian speakers. Authorities have sought to address this gap in recent years through more investments in local Russian-speaking media initiatives. They also moved to block channels linked to the Russian state in an effort to curtail propaganda related to its full-scale military invasion of Ukraine.

Italy’s media environment boasts a diversity of viewpoints. However, newsrooms covering sensitive stories operate in a precarious environment, and reporting on organized crime and similar issues can elicit serious threats. Historically high levels of media partisanship, the lack of a strong self-regulatory system, and low levels of professionalism have also undermined trust in Italian media. Powerful players in the television market have used their media platforms to pursue political interests, including media mogul Silvio Berlusconi, who was able to leverage media assets during his various bids for public office.

As media organizations continue to navigate transformations rocking the industry, defending independent media—a crucial cornerstone of democracy—calls for creative solutions. The stakes are particularly high in Hungary and Poland, where political interference through media capture and other legal and institutional maneuvers have become a sign of democratic decline. Under these conditions, powerful actors are successfully exploiting resources, attention, and trust to their advantage, while undermining critical coverage that holds them to account.

The Search for Financial Viability

A vibrant, independent press cannot function without strong economic foundations. Yet financial survival is top of mind for many media organizations that are scrambling to find solid footing amid global market upheavals.1 Local newspapers have been particularly vulnerable to these shifts. Moreover, disturbing developments in the region show that when economically weakened, the foundations underpinning media’s role in democracy can be easily subverted to undermine editorial autonomy and exert political influence.

Digital disruption and outsized competition from big technology platforms have rocked the business model that once underpinned the sustainability of the media industry. As audiences increasingly turn to online platforms, traditional income sources based on commercial advertising and print sales have steadily declined. According to the World Advertising Research Center, global advertising spending in print newspapers in 2023 is set to represent less than a fifth of what it was in 2007.2

While larger media outlets in Europe have offset some of these losses through digital advertising, the lion’s share of digital-advertising income gets hoovered up by big technology companies, rather than bolstering the finances of individual media outlets. More newspapers are adapting to changing conditions by diversifying sources of income and pursuing online subscription models, with varying degrees of success.

Newsrooms under financial pressure

Even in countries that boast wealthy markets and strong traditions of local reporting, technological disruptions and commercial pressures have prompted media organizations to adopt solutions that can undermine the quality of their journalism. Some publishers cut costs and consolidated their market positions by purchasing smaller outlets and merging editorial teams, raising concerns about reduced coverage and declining diversity. In countries such as Germany, where regional and local outlets play an important role within the country’s federally organized system, experts worried about the democratic risks of cost-saving strategies that reduce scrutiny of local governance.

Deutsche Welle employees hold a demonstration against the international public broadcaster’s cost-cutting plans in Berlin, Germany, in May 2023. (Photo credit: Jörg Carstensen/dpa/Alamy Live News)

Job precarity is a problem in markets where media houses are no longer able to hire as many people to sustain high-quality reporting. The rising number of freelance journalists working without guarantees of a stable income contributes to greater insecurity in the profession, especially in environments such as Poland or Italy, where investigative reporters frequently face costly lawsuits. According to recent appraisals, for example, freelancers sometimes barely fetched more than €20 ($22) for 1,000-character articles in major Italian newspapers.3 Giovanni Zagni, editor in chief of the fact-checking website Pagella Politica, explained: “You have either big legacy media that struggle to keep up with the level of wages, or really small independent media that have to find ways to either circumvent [labor] laws or pay really substandard wages.”4 Such conditions threaten to accelerate an exodus of talented people who no longer see journalism as a viable career.

The dangers of deep pockets and vested interests

In some countries, economic conditions have heightened concerns about accelerating market concentrations among business moguls with interests outside the sphere of media.

In France, the public has grown skeptical about leading outlets that have landed in the hands of wealthy industrialists with business interests in industries like defense, construction, telecoms, and transportation.5 In a Senate inquiry launched in 2021, experts warned that France’s outdated legislation was no longer able to guarantee pluralism across different media sectors.6 Controversy has especially surrounded the conservative billionaire Vincent Bolloré, who has become notorious for editorial meddling in the growing number of outlets that his family conglomerate owns, including trying to silence coverage about his business dealings in Africa.7 Ahead of the 2022 election campaign, his channel CNews gave a prominent television platform to far-right pundit Éric Zemmour, which helped to propel his presidential bid.8 “Concentration is not new,” noted French communications professor Philippe Bouquillion, “but what is new in France is the fact that a main shareholder tried to influence political content. And this is quite new at such a big scale in the country.”9

“Concentration is not new. But what is new in France is the fact that a main shareholder tried to influence political content.”

Attribution

Philippe Bouquillion, professor of communication

The democratic consequences are even more acute when media ownership becomes captured by ruling-party interests. The departure of foreign investors in less favorable environments can create a vacuum that leaves more space for government-friendly actors to enter the scene. In Hungary, a series of media takeovers by wealthy businesspeople aligned with the ruling party, Fidesz, has enabled an unaccountable government to flourish by dominating media at the local and national level. In an unprecedented move in late 2018, hundreds of progovernment media outlets, including newspapers and television and radio stations merged under a nonprofit conglomerate called the Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA). The government declared the merger to be of “national strategic importance” to exempt it from competition laws.10

In Poland, state-owned companies have taken over outlets in line with a professed strategy by the nationalist Law and Justice (PiS) government to “repolonize” the media landscape. In 2020, the state-run oil company Orlen purchased Polska Press, which includes leading regional newspapers, magazines, and hundreds of online portals, from its German owners. Editorial changes followed soon after.11

Politicized market distortions threaten independent media

To prevent market failures in the industry, some governments are looking to bolster outlets that are struggling financially. But publicly funded support can also threaten editorial independence if not distributed in a fair and transparent way. Amid dwindling private advertising revenues, preferential state advertising has emerged as a tool of choice for ruling parties that seek to manipulate the landscape in self-serving ways.

In Hungary and Poland, public entities have actively skewed the market by directing the bulk of state advertising to media outlets that provide friendly coverage of the government, while boycotting independent media that scrutinize it.12 “It means we just have much less money than we should get in fair systems. We have fewer journalists, less money to run stories, less money to run the business,” said Łukasz Lipiński, deputy editor in chief of the Polish weekly magazine Polityka.13 Mihály Hardy, the editor in chief of the independent radio station Klubrádió in Hungary, reflected on how the station’s successful commercial operations changed when Viktor Orbán came to power in 2010: “Klubrádió lost its advertising revenues drastically: within six months it was reduced to 10 percent of what it used to be.”14 While the state is the biggest advertiser in Hungary, media experts also noted that commercial players are more unlikely to place advertising in independent media, for fear of repercussions such as tax investigations.15

In contexts where the cards are heavily stacked against them, the quest to find alternative means to survive is a crucial battle for independent media that provide essential information and dare to scrutinize those in power. Some independent outlets have been able to leverage their strong reputations to elicit financial support from audiences who trust them, as seen in the following case study about Hungarian media.

The Search for Audiences & the Risk of Information Vacuums

The digital era offers a wealth of new opportunities but also challenges for news organizations that are struggling to bridge generational divides, and reach diverse audiences across fragmented media environments.

An underlying challenge stems from the acute shift in consumption habits. Younger generations are increasingly flocking to an ever-changing landscape of social networks. Organizations such as the Reuters Institute have been tracking this trend: in its 2022 Digital News Report, it found that 39 percent of 18-to-24-year-olds across 12 markets including Germany, France, and Italy use social media as their main source of news, compared to 34 percent who opt to go directly to a news website or app.16

When independent media outlets are unable to represent or reach certain segments of the population, purveyors of false and misleading information are more able to influence public debate and interfere with people’s ability to make informed choices.

Shifting business models spark anxiety about information inequalities

As more newspapers look to build relationships with paying audiences online, some media experts worry that incentives to target more lucrative audiences through tools like paywalls threaten to widen the gap between the “information rich” and the “information poor.” However, evidence of growing inequalities is not clear-cut in countries where paywalls are a common feature, but where alternative sources of quality news are also still available online for free. An analysis of European survey data by the Reuters Institute suggests that “as paywalls become more commonplace, public service media will be especially important for keeping information inequalities low.”17

Where public service broadcasters are no longer able to fulfill their mandate and maintain editorial independence, underserved audiences are particularly vulnerable to consuming lopsided news. This concern is perhaps most relevant in Hungary, given the dominance of progovernment voices in the media landscape, including the government-controlled state broadcaster. “If a paywall is applied, the general public cannot have access to these important articles, and this is something that narrows down the pool [from] which the average Hungarian, anyone, can get information from,” said Emese Pásztor, director at the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union.18 For this reason, many independent outlets in Hungary that are fulfilling a public service function are still opting against strict paywalls. “At Telex we feel this responsibility [that] if we put the content behind a paywall, then not everybody will afford to consume fact-based journalism,” explained Veronika Munk.19

A protester holds a placard with the symbol of Poland’s ruling party Law and Justice (PiS) pasted onto the logo of public television broadcaster TVP at a demonstration against a proposed media advertising tax in Warsaw, Poland, in February 2021. (Photo credit: Attila Husejnow / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)

Navigating gaps between different consumption habits

Public broadcasters and local press outlets are especially struggling to reinvent themselves to appeal to younger generations—a concern highlighted by experts interviewed in France and Italy. Building brand loyalty and monetizing engagement with the next generation of news consumers also remains a difficult quest for newspapers worried about their bottom line. Robin Alexander, deputy editor at the newspaper Die Welt in Germany, reflected on the difficult task of bridging these gaps on social media platforms: “Now you have younger people in Germany, for whom Instagram is a primary source. So, do we have an obligation to be on Instagram if we want to reach the audience? I think so, but if we do not have a mechanism to make money out of it, that is a problem.”20 While publishers increasingly recognize the need to take content to where audiences are, financial incentives to do so are lacking.

“We feel this responsibility [that] if we put the content behind a paywall, then not everybody will afford to consume fact-based journalism.”

Attribution

Veronika Munk, co-founder of Telex in Hungary

On the other hand, older generations continue to rely on traditional sources of news: a 2022 Eurobarometer survey of participants in EU countries found that 85 percent of respondents over age 54 primarily get their news from television.21 In some cases, well-established consumption habits can entrench “information bubbles” that limit exposure to a multiplicity of perspectives. Estonia, for example, has a significant Russian-speaking minority, and generations that grew up under the Soviet Union have long watched Russian state television. The Russian regime’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 heightened concerns about the prevalence of propaganda disseminated by Russian media. The Estonian government acted quickly to ban the retransmission of Russia’s state-backed channels, although people can still access these channels near the border, via antenna.22 In turn, the Estonian government has also increased investments in Russian-speaking media to promote alternative viewpoints among this segment of the population.

The following case study examines how public service media are addressing information gaps in Estonia and Germany.

The Battle for Public Trust

As misinformation and disinformation compete with factual reporting for people’s attention, maintaining credibility as a trusted source has become a crucial challenge for news organizations. Growing distrust of media has given way to outright antagonism, and journalists are increasingly vulnerable to online abuse and physical attacks. During COVID-19-related protests in Germany, Italy, and France, for example, members of the public insulted, spat at, and physically attacked journalists covering the events.23

Levels of trust in media vary among countries as well as among types of outlets. According to the 2022 Flash Eurobarometer survey, public service broadcasters are the most trusted sources of news in Estonia (67 percent), Germany (62 percent), France (49 percent), and Italy (45 percent), followed by the written press (including online) and private broadcasters.24 The picture is more fragmented in Poland, where the public broadcaster functions largely as a mouthpiece for the ruling party; Polish respondents listed private broadcasters as their most trust sources of news (43 percent), followed by people, groups, or friends on social media or messaging platforms (26 percent). In Hungary, where the public broadcaster has been effectively captured, respondents first listed people or groups on social media or messaging platforms (25 percent), followed by other online news platforms (22 percent), which tied with public broadcasters (22 percent). These differences suggest that trust in media is low in landscapes with greater polarization and media bias, prompting people turn to less formal sources of news to confirm their views.

Delegitimizing credible media

News organizations have increasingly found themselves in the crossfire of populist politics, which capitalize on antiestablishment frustrations and people’s distrust of traditional institutions, including the media.25 In Germany, despite high levels of overall trust in traditional media, distrust in “Systemmedien” (“media of the system,” a pejorative term for public broadcasters) has coincided with the rise of the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD), which is especially strong in the eastern states.26 AfD has denigrated public service media and targeted their funding, while maximizing attention-seeking tactics to garner media coverage.27 “As a party, they are quite clever in using, for example, public service media and the entire media system to their advantage, while at the same time officially being opposed to it,” explained media journalist Steffen Grimberg, who sees shrinking trust as one of the biggest threats for media in Germany.28

Strategies built on destroying trust in media and other democratic institutions have emboldened leaders who seek to evade public scrutiny and impose their own narratives. Attacks reached new heights in Hungary, where ruling party Fidesz has actively cast independent journalists as adversaries rather than essential democratic counterweights. Fidesz relies on a loyalist media machine that includes the national news agency, the public broadcaster, regional outlets, and social media influencers, to propagate harmful narratives. In January 2023, investigative outlet Átlátszó was targeted in what appeared to be coordinated smear campaign across several progovernment media outlets that accused it and its journalists of serving foreign interests.29 “They want to attack our credibility…it means that polarization is getting worse. We want to talk to all of the Hungarian audiences, and we do not want to talk exclusively to the opposition. That is why these smear campaigns are happening,” said Tamás Bodoky, editor in chief of Átlátszó.30 The term “Dollar media” has increasingly been used by Fidesz-supportive media and influencers to smear the few independent outlets that produce investigative reporting and critical journalism. The term is meant to advance the false implication that independent outlets are beholden to the objectives of foreign donors.

“They want to attack our credibility…it means that polarization is getting worse.”

Attribution

Tamás Bodoky, editor in chief of Hungarian investigative outlet Átlátszó

An eroding middle ground

In turn, concerted political attacks against independent media can undermine a shared sense of facts, and consequently, the ability of media to engage in constructive public debate. In Hungary, political polarization has entrenched audiences into two opposed camps based on who trusts what. Ervin Gűth, who runs a local newsletter in the southern city of Pécs, explained how this divisive line operates even at the local level: “There is a huge proportion of the population that is never going to read my newsletter, because there is an independent label on it. If you put the label ‘independent,’ it means that you are against Fidesz.”31

In Poland, independent media are similarly left fighting a perception that they are opponents of the ruling party rather than sources of information: “We cannot build a public trust with people who are on the other side because they do not trust us even with existing facts. Building public trust sounds very nice, but in the reality of a very deeply polarized society, it is not that easy. And there are some media outlets that are actually thriving on that,” noted Łukasz Lipiński, deputy editor in chief of Polityka magazine.32 Since coming into power in 2015, government pressures against independent media and increased control of media narratives within public broadcasters have further polarized a media landscape that largely mirrors ideological conflicts between the ruling party and its opponents.33

Meanwhile, the picture remains more optimistic in countries where politics are still largely driven by consensus and deliberation, despite a fringe of people that reject mainstream media. Robin Alexander, political reporter for the newspaper Die Welt, suggested that “one big advantage of Germany is that our society is not as split. You do not have a situation where from a normal person’s media consumption, you could predict their vote.”34 Within a less polarized landscape, a middle ground can still foster healthy debate across politics, society, and the news media.

The effects of weak editorial standards, conflicts of interest, and lack of transparency

Observers also criticize shortcomings in the media industry itself to explain the erosion in public trust. In a country where news media has been closely intertwined with politics, Italy’s high levels of media partisanship and weak levels of professionalism continue to undermine audience trust. According to the Reuters Institute’s Digital News Report in 2022, only 13 percent of Italian poll respondents think that media are independent from undue political or government influence.35 Media experts in Italy pointed to ingrained newsroom cultures and polemic-driven news agendas, highlighting the need to better educate journalists about the responsibility of the press to pursue a watchdog role, defend transparency, and adapt to changing user needs. “If Italian journalists do not change, you cannot change the relationships that you have with your users,” argued Sergio Splendore, who teaches a course about journalism, media, and politics at the University of Milan. However, increased financial pressure on legacy media has limited investments in innovation and quality news online. The websites of major Italian newspapers have especially faced problems with poor quality, as they are confronted with pressure to cover relentless news cycles despite strained editorial resources.

In France, ownership concentration among big industrialists has given way to concerns among the public about potential conflicts of interest. Only 21 percent of respondents in France believe that media are independent from undue political or government influence, and just 19 percent think that they are independent from undue business or commercial influence, according to the same 2022 Reuters Institute study.36 According to Augustin Naepels of the digital news site Les Jours, “one of the main reasons for this mistrust is the lack of transparency and independence from media. And this is almost a cliché…the perception of financial dependence on big businessmen is really problematic.”37

However, some independent digital outlets have begun to experiment with new models focused on quality, transparency, and a renewed relationship with audiences. The following case study describes how some French and Italian digital-first outlets have worked against the grain to build credibility.

Investigating the Truth & Efforts to Silence it

Media outlets navigate a treacherous environment when pursuing stories that scrutinize matters of public interest. Powerful actors are opting for more covert tactics to stifle reporting that unearths uncomfortable truths, such as denying journalists access to information and using baseless legal threats and actions to intimidate their targets in media.

Perpetrators are also moving beyond defamation lawsuits—which have been common for years—to a wider array of accusations to harass targets. Civil society organizations have increasingly raised the alarm about SLAPP (Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation) lawsuits targeting journalists and media outlets across the region. Typically launched by powerful and moneyed individuals, SLAPPs are specifically intended to intimidate and silence acts of public participation, including public interest journalism. They also threaten to entangle targets in endless litigation. According to the Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE), SLAPP cases are particularly effective where the rule of law is lacking, but laws can be exploited even within robust environments.38

Abusive legal attacks drain investigative reporting

Baseless lawsuits are taking a toll on many cash-strapped news outlets. In interviews, media professionals described the energy and resources it takes to tackle such cases, often distracting them from doing their work. In Poland, a country where SLAPP cases have especially proliferated, the daily Gazeta Wyborcza has braced itself for a barrage of legal threats from public officials, state institutions, and companies.39 “We have to fight 24/7. We have only two in-house lawyers to work on that. It takes time, energy, consumes resources, and also the resources of our journalists who must respond to SLAPPs while they should continue their real job,” explained Piotr Stasiński, a longtime editor at the paper.40

The range of laws and pressure tactics powerful actors are harnessing to harass public-interest reporters is growing. According to the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (TASZ), which provides legal aid and pursues strategic litigation in defense of the free press, less straightforward cases filed against news outlets in Hungary have sought to use European Union (EU) data-protection regulations to silence coverage. Another recent case involves accusations of criminal violation of copyright.41 In late 2022, a criminal probe launched by tax authorities increased pressure on one of the last defiant media moguls in Hungary, Zoltán Varga, whose Central Media Group owns the independent news outlet 24.hu. This came on top of smear campaigns, targeted surveillance, and other efforts to sway the outlet’s editorial line.42

Abusive defamation laws against media remain common, and criminal defamation is frequently wielded against the media in Poland and Italy. Given financial weaknesses facing many cash-strapped outlets and journalists, the impact of these threats on self-censorship is most likely underreported. In Italy, where freelancers are often those doing hard-hitting investigations, the lack of legal and financial backing can deter many from pursuing sensitive stories. According to Cecilia Anesi, investigative reporter and co-founder of the Investigative Reporting Project Italy (IRPI), “The result of all that is that both media outlets and journalists avoid reporting on certain issues because of the pressure that comes out of it.” Moreover, civil lawsuits can be particularly worrying for the survival of media companies, given that they can entail excessive damages: “If you are found guilty, they can take away all the finances of the media company, meaning no more money to sustain the newsroom and production,” noted Anesi.43

Declining judicial independence forecasts a bleaker outlook for journalists investigating sensitive political issues in Poland and Hungary. While Gazeta Wyborcza mostly still wins cases that end up going to court, the Law and Justice party’s encroachment on judicial independence is affecting the paper’s success rate in fighting certain cases. “It is like a domino effect,” said Piotr Stasiński, describing the biased appointment of judges by the now-politicized National Council of the Judiciary. “The impact on us is that we start losing cases, which are obvious cases that we should win if judges were really independent.”

In Hungary, higher-level courts tend to favor the government, especially the Constitutional Court. “Before we go to the European Court of Human Rights, we have to exhaust the Hungarian Constitutional Court. And that is a very long and not very successful process for us,” said Dalma Dojcsák of TASZ.44

Government secrecy constrains access to information

Despite freedom of information (FOI) laws, media professionals also described a variety of barriers to obtaining and using information from public bodies and officials. These ranged from increasing frequency of the “for official use” stamp on state documents in Estonia, to unanswered requests for information in Italy. Barriers for independent outlets in Hungary and Poland have become increasingly impenetrable. “The government is denying us information which actually should be public legally. They are canceling accreditation or blocking entrance to certain events. They are making some events open only to journalists who are friendly to government,” explained Łukasz Lipiński of Polityka magazine in Poland.45

These bureaucratic obstacles have a particularly damaging effect on investigative work that relies on timely data and public records. According to András Pethő, co-founder of the investigative outlet Direkt36 in Hungary, the barriers have increased compared to a decade ago: “You can still file public-information requests with the government or other state organizations. Officially, they are supposed to give you records and data, but that hardly ever happens, because they always come up with excuses. And then you have to go to court, and that takes time, which is a big barrier.”46

Even when information requests are pursued in court, the process can be drawn out and the outcome is often unsatisfying. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, TASZ and the independent outlet Telex launched a lawsuit challenging a government rule that prevented independent media from entering hospitals. The Supreme Court eventually ruled that hospital directors, not the government, could decide whether to grant access to journalists. However, a government decree introduced days later handed that responsibility back to a government office, effectively abrogating the decision.47

“We have to fight 24/7.”

Attribution

Piotr Stasiński of the Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza

Surveillance tools endanger the confidentiality of journalistic sources

In addition to legal and institutional tactics, there have been revelations in several EU countries about authorities targeting independent journalists with advanced spyware technologies.48 The threat of surveillance can prompt sources to remain silent for fear of being identified. In 2021, a collaborative investigation found that Hungarian journalists were amongst those targeted by Pegasus, a sophisticated spyware tool developed by Israeli company NSO Group.49 A forensic analysis of devices by nongovernmental organizations revealed that targets included journalists at Direkt36 and people close to Zoltán Varga of Central Media Group.

Although investigations could not directly confirm who deployed the tool against identified targets, the case heightened concerns about politically motivated surveillance by Hungarian authorities under permissive national security provisions, and highlighted the difficulties in effectively investigating and remedying these abuses. While the Hungarian government eventually acknowledged purchasing the spyware, authorities maintained that it had used it in accordance with Hungarian law.50 To expose the Hungarian government’s invasive surveillance practices and counter politically motivated abuses, in January 2022 TASZ announced the launch of domestic and international legal procedures against the Hungarian state and NSO Group, in the first case bought by Pegasus victims against an EU state.51 In turn, the EU has come under increased pressure to tighten safeguards around the use, sale and acquisition of spyware, and effectively address abuses within the bloc.52

Leave a Reply